The Fullness of Words

Adrienne Rich

Sources

The Heyeck Press, Woodside, 1983

The poem ends with the expressed desire to rest "among the beautiful and common weeds" but recognizes there is no such rest.

A phrase has occurred at intervals throughout the sequence: an end to suffering. We are informed in a note as to its origins:

The phrase an end to suffering was evoked by a sentence in Nadine Gordimer's Burger's Daughter: "No one knows where the end of suffering will begin."We come back to Rich's conclusion: "When I speak of an end to suffering I don't mean anesthesia." She turns to the specificity of place and identity, themes she has carried throughout.

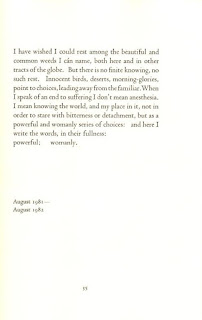

When I speak of an end to suffering I don't mean anesthesia. I mean knowing the world, and my place in it, not in order to stare with bitterness or detachment, but as a powerful and womanly series of choices: and here I

write the words, in their fullness:

powerful; womanly.

A block of prose gives way to poetry. A line break falls on "I" and spacing between "powerful" and "womanly" return us to the typography of the preceding sections to conclude that the speaking self is powerful and mediated through the fullness of words.

A block of prose gives way to poetry. A line break falls on "I" and spacing between "powerful" and "womanly" return us to the typography of the preceding sections to conclude that the speaking self is powerful and mediated through the fullness of words.

Meditating on the spaces between words, I came back to Olsen's 1950 observations in "Projective Verse" on breath (and spirit) and the place of the typewriter in the disposition of the words on the page.

What we have suffered from, is manuscript, press, the removal of verse from its producer and its reproducer, the voice, a removal by one, by two removes from its place of origin and its destination. For the breath has a double meaning which [L]atin had not yet lost.Time is what Rich chooses to mark. Dates we take to be the span of composition — a year. There is in these poetics no place without time. No words without a fullness of history.

The irony is, from the machine has come one gain not yet sufficiently observed or used, but which leads directly on toward projective verse and its consequences. It is the advantage of the typewriter that, due to its rigidity and its space precision, it can, for a poet, indicate exactly the breath, the pauses, the suspensions even of syllables, the juxtapositions even of parts of phrases, which he intends. For the first time he can, without the convention of rime and meter, record the listening he has done to his own speech and by that one act indicate how he would want any reader, silently or otherwise, to voice his work.

And so for day 2240

30.01.2013